As Extensive Rain Floods New England and New York State, Temperatures Over 110 Will Cook The Southwest All Week

The entire country is completely unprepared to deal with what is now the new normal.

Christopher Flavelle and Rick Rojas, New York Times, July 11, 2023

This week’s flooding in Vermont, in which heavy rainfall caused destruction even miles from any river, is evidence of an especially dangerous climate threat: Catastrophic flooding can increasingly happen anywhere, with almost no warning.

And the United States, experts warn, is nowhere close to ready for that threat.

The idea that anywhere it can rain, it can flood, is not new. But rising temperatures make the problem worse: They allow the air to hold more moisture, leading to more intense and sudden rainfall, seemingly out of nowhere. And the implications of that shift are enormous. . . .

The federal government is already struggling to prepare American communities for severe flooding, by funding better storm drains and pumps, building levees and sea walls and elevating roads and other basic infrastructure. As seas rise and storms get worse, the most flood-prone parts of the country — places like New Orleans, Miami, Houston, Charleston or even areas of New York City — could easily consume the government’s entire budget for climate resilience, without solving the problem for any of them. . . .

[T]he country lacks a comprehensive, current, national precipitation database that could help inform homeowners, communities and the government about the rising risks from heavy rains.

In Vermont, the true number of homes at risk from flooding is three times as much as what federal flood maps show . . . That so-called “hidden risk” is staggeringly high in other parts of the country as well. In Utah, the number of properties at risk when accounting for rainfall is eight times as much as what appears on federal flood maps, according to First Street. In Pennsylvania, the risk is five and a half times as much; in Montana, four times as much. Nationwide, about 16 million properties are at risk, compared with 7.5 million in federally designated flood zones.

The result is severe flooding in what might seem like unexpected places, such as Vermont. . . . In March, heavy rain caused federal disaster declarations across six counties in Nevada, the driest state in the country. . . .

Last year, a deluge of rain touched off flash floods that surged through the hollows of eastern Kentucky. . . .

The communities scattered through the Appalachian Mountains are familiar with flooding . . . But the ferocity of that flood left longtime families bewildered. “We went from laying in bed to homeless in less than two hours,” Gary Moore, whose home just outside Fleming-Neon, Ky., was destroyed, said in the days after the flood.

The floods aggravated by climate change were also compounded by the lingering effects of coal mining, as the industry that once powered communities receded, leaving behind stripped hillsides and mountains with their tops blown off. The loss of trees worsened the speed and volume of rain runoff. . . .

As the threat from flooding and other climate shocks gets worse, the federal government has increased funding for climate resilience projects. The 2021 infrastructure bill provided about $50 billion for such projects, the largest infusion in American history.

But that funding still falls far below the need. . . .

Montpelier, Vermont

Justine McDaniel and Joanna Slater, Washington Post, July 11, 2023

Intense flooding across Vermont trapped residents in their homes, washed out roads and set off widespread rescue efforts, a crisis that officials warned would continue at least through the week’s end.

More than 100 people had been rescued statewide by Tuesday morning, while crews on boats and in helicopters searched for others who were stranded in the rural, mountainous state, officials said. Rescuing those who were trapped was expected to take several days, state authorities said, and they feared that more rain starting Thursday could bring further devastation.

Flash floods Monday from heavy rainfall turned to river flooding Tuesday as the rain stopped and rivers across the state rose, including in the state capital, Montpelier, and throughout the Green Mountains. Some surpassed major flood stage at record-breaking levels, and a few dams neared capacity . . .

The extent of the storm’s damage to roads, buildings and other infrastructure remained far from clear, but thousands of people had lost homes and businesses, and countless roads had been washed out . . .

Residents described seeing waterfalls, mudslides, blocked roads and washed-away bridges. . . .

[O]fficials were bracing for more rain later this week. Vermont’s swollen rivers were set to drop below minor flood stage before Thursday’s showers, but in areas that saw the worst flooding, more flash floods prompted by late-week rain couldn’t be ruled out . . .

The storms began Sunday and hit Vermont, New York, Connecticut and other spots in the Northeast, killing one person in the Hudson Valley. . . .

In Vermont, the storms dumped six to nine inches of rain — in some places, more than two months’ worth — on parts of the state from late Sunday to early Tuesday. . . .

The Winooski River, which flows through Montpelier, crested above 21 feet, higher than during Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 and nearly four feet above major flood stage, Duell said. . . .

Rainfall earlier in the month had already soaked the ground, priming the state for floods by making the soil unable to absorb the latest deluge. . . .

Waterbury, Vermont

Barre, Vermont

Jenna Russell, New York Times, July 11, 2023

“It was an apocalyptic feeling,” said Dylan Woodrow, 29, of Montpelier, who paddled his kayak through more than three feet of water there on Tuesday, asking people stranded in second-floor apartments if they needed help. . . .

The two-day storm dumped more than eight inches of rain on some parts of Vermont. The storm also swamped some areas in New York State, where, in the course of just 24 hours on Sunday, more than twice as much rain fell than is typical for the entire month of July, according to the National Weather Service. . . .

Many business owners who waited impatiently to regain access to their stores on Tuesday soon found their worst fears realized. Bob Nelson, who owns a 40-year-old hardware store in downtown Barre estimated that he had lost about $300,000 worth of inventory in the store’s flooded basement, which his insurance does not cover. He said the flooding was worse than after Tropical Storm Irene. “In 2011, we had almost four feet of water in the basement,” he said. “We didn’t have nine feet like we have now.” . . .

And where there is not rain and flooding, there is intense heat.

Jeff Goodell is the author of The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet. From his July 8, 2023, essay in the New York Times:

In 2019, I happened to be visiting Phoenix on a 115-degree day. I had a meeting one afternoon about 10 blocks from the hotel where I was staying downtown. I gamely thought I’d brave the heat and walk to it. How bad could the heat really be? I grew up in California, not the Arctic. I thought I knew heat. I was wrong. After walking three blocks, I felt dizzy. After seven blocks, my heart was pounding. After 10 blocks, I thought I was a goner.

That experience led me to spend the next three years researching and reporting a book about the dangers of extreme heat and how rising temperatures are reshaping our world. I talked to doctors about how when the core temperature of our bodies rises too high, the proteins in our cells begin to unravel. I sailed to Antarctica to see how changes in ocean temperature accelerate the melting of glaciers, causing seas to rise and flooding coastal cities around the world. I talked to people in the slums of India and in oven-like apartments in Arizona and in stifling hot garrets in Paris. I trapped mosquitoes in Houston and learned about how the spread of dengue fever and malaria is altered by hotter temperatures. I talked to engineers about how heat bends railroad tracks and weakens bridges. In short, I thought I had a pretty good idea about the impacts of extreme heat in our world.

And then, in mid-June, a few weeks before publication of my book, a heat dome settled over the entire Southwest as well as Mexico, breaking temperature records and turning asphalt to mush. I had recently moved to Austin, Texas. Yes, Texas is a hot place. But this was different. We’re talking about a heat index — the combination of temperature and humidity — as high as 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

Events disturbingly similar to what I had reported on in other places several years earlier were playing out in real time around me, like hikers dying of heatstroke and thousands of dead fish washing up on Gulf Coast beaches (hotter water contains less oxygen, making it difficult for fish to breathe). The red-faced desperation on the faces of homeless people living beneath an overpass near me was spookily evocative of the red-faced desperation I’d seen on the faces of people in India and Pakistan. . . .

If you are lucky enough and well-off enough, perhaps there is no sense that a life-threatening force has invaded your world. This past week, records were set or tied on four consecutive days as the hottest days ever recorded on Earth. . . .

[L]iving under the Texas heat dome has reinforced my view that we have to be cleareyed about the scope and scale of what we are facing. The extreme heat that is cooking many parts of the world this summer is not a freakish event — it is another step into our burning future. The wildfires in Canada, the orange Blade Runner skies on the East Coast, the hot ocean, the rapidly melting glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica and the Himalayas, the high price of food, the spread of vector-borne diseases in unexpected places — it is all connected, and it is all driven by rising heat. . . .

Extreme heat is the engine of planetary chaos. We ignore it at our peril. Because if there is one thing we should understand about the risks of extreme heat, it is this: All living things, from humans to hummingbirds, share one simple fate. If the temperature they’re used to — what scientists sometimes call their Goldilocks Zone — rises too far, too fast, they die.

Jacey Fortin and Mary Beth Gahan, New York Times, July 11, 2023

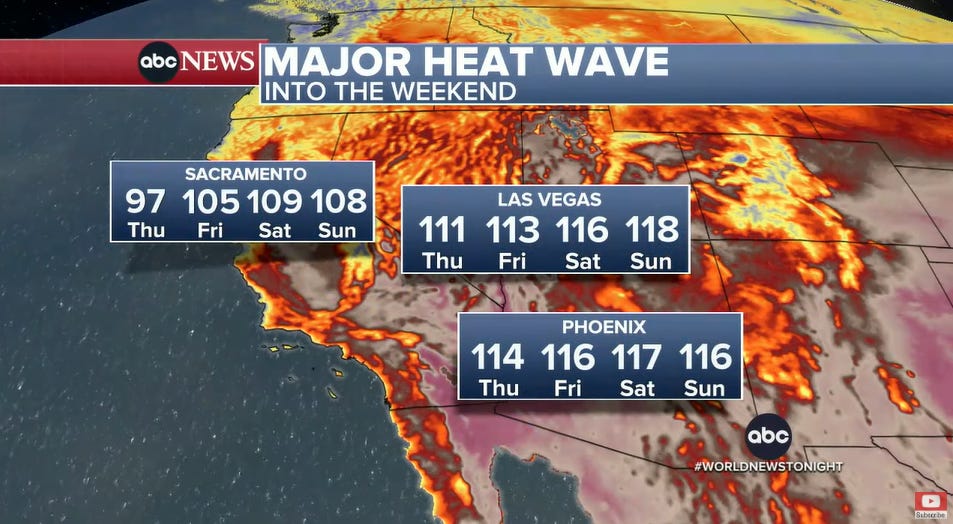

A heat dome of high pressure that has parked over New Mexico and West Texas, and the soaring temperatures across much of the South, from Florida to California, are expected to last at least two more weeks. Experts estimate that more than 50 million people across the United States live in areas expected to have dangerous levels of heat. . . .

For people without shelter, the relentless heat is particularly dangerous.

Bob Feinman, the vice chair of Humane Borders, a nonprofit organization in Tucson, said that migrants walking through the Arizona desert from the Mexico border had been in dire need of water during the heat wave. Lately, the water tanks that the organization has placed in high-traffic areas have had to be refilled more frequently. . . .

The high temperature was expected to approach 109 degrees in Phoenix and 105 in Tucson, and similar triple-digit temperatures were likely to continue for at least a week, possibly approaching record-breaking levels by the weekend.

The water off the coast of Florida is 90F.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/12/climate/florida-ocean-temperatures-reefs.html